Articles with tag “Energy”

Beyond Local Energy: Delivering Public Power

Rhetorically, Labour has fully committed itself to fighting climate change and recognises that public ownership of energy will be vital in doing so. However, as yet they do not have a practical plan for achieving this. As I have explained previously, Labour’s policy proposals on green energy and climate ...

Beyond Slogans: Sketching a Green New Deal

The last few months have seen an impressive shift in public discussion on how to address climate change. Thanks in large part to newly-elected democratic socialist congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the concept of a “Green New Deal” has come to the fore. This marks a significant move away from previous policy ...

Labour’s Energy Plans: Technically Questionable, Politically Vacuous

During last year’s conference, the Labour Party made headlines with its seemingly bold promises on energy and climate change. These included a massive build-out of wind turbines, solar panels, and a housing retrofit programme. We were promised that these pledges would be elaborated on in a report to be ...

Ownership and Markets in Energy

One of the most popular elements of Labour’s 2017 manifesto was the pledge to return energy to public ownership. At last year’s conference John McDonnell said “Rail, water, energy, Royal Mail—we’re taking them back”. This makes it sound like he’s pledging to renationalise energy, but examining Labour’s manifesto policies it quickly becomes clear that he is either being deliberately misleading or displaying a stunning lack of understanding of how the energy sector functions in this country. The fragmented energy system Labour propose would fail to address the key problems with privatisation as it would leave the electricity market in place.

On Climate Change, Ashton Beats Corbyn

Following on from the success of Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders in the UK and US, Niki Ashton has been presenting herself as the left-wing candidate in the current NDP leadership race. Recently she published a commitment to “environmental justice” which stacks up very well against Corbyn’s disappointing commitments on energy and climate change.

Labour Policy Responses: Environment, Energy and Transport

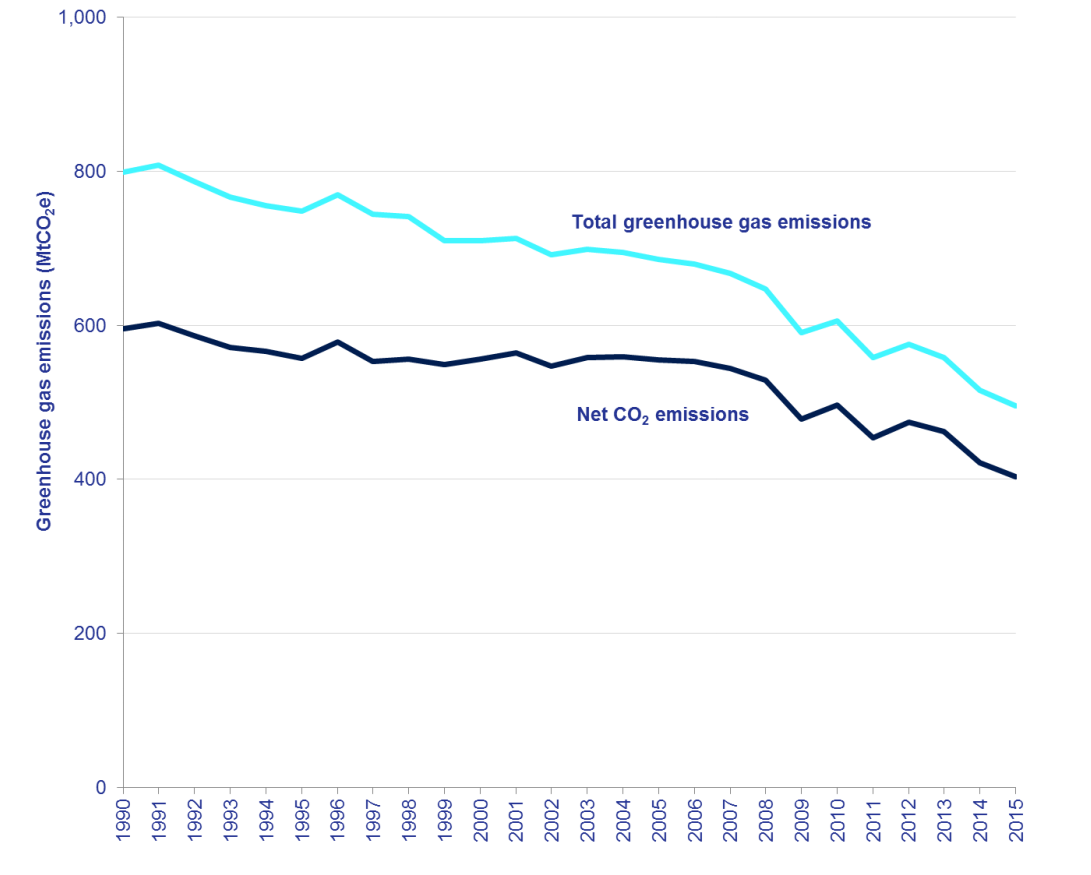

The NPF document rightly identifies climate change as one of the greatest challenges of the century. However, beyond this, it has little to say. It refers to the Paris Agreement of 2015, but does not acknowledge that the stated goal of keeping warming below 2°C, or even 1.5°C, is not going to be achieved with the emissions commitment which were made. Nor is the magnitude of the challenge of keeping temperatures below those limits recognised. It seems inconceivable that it could be done without state-directed economic planning on a scale previously unseen in the West during peacetime.

A 21st Century Energy Policy, Part 4: The Institutions to Make it Happen

As discussed in Part 3, transition to a low-carbon economy is a massive task which will require extensive government intervention. A great deal of work will be needed to develop the capacities for the state to make such investments and the proposals made thus far by Jeremy Corbyn are wholly inadequate. What is needed is a nationalised, vertically integrated electricity sector.

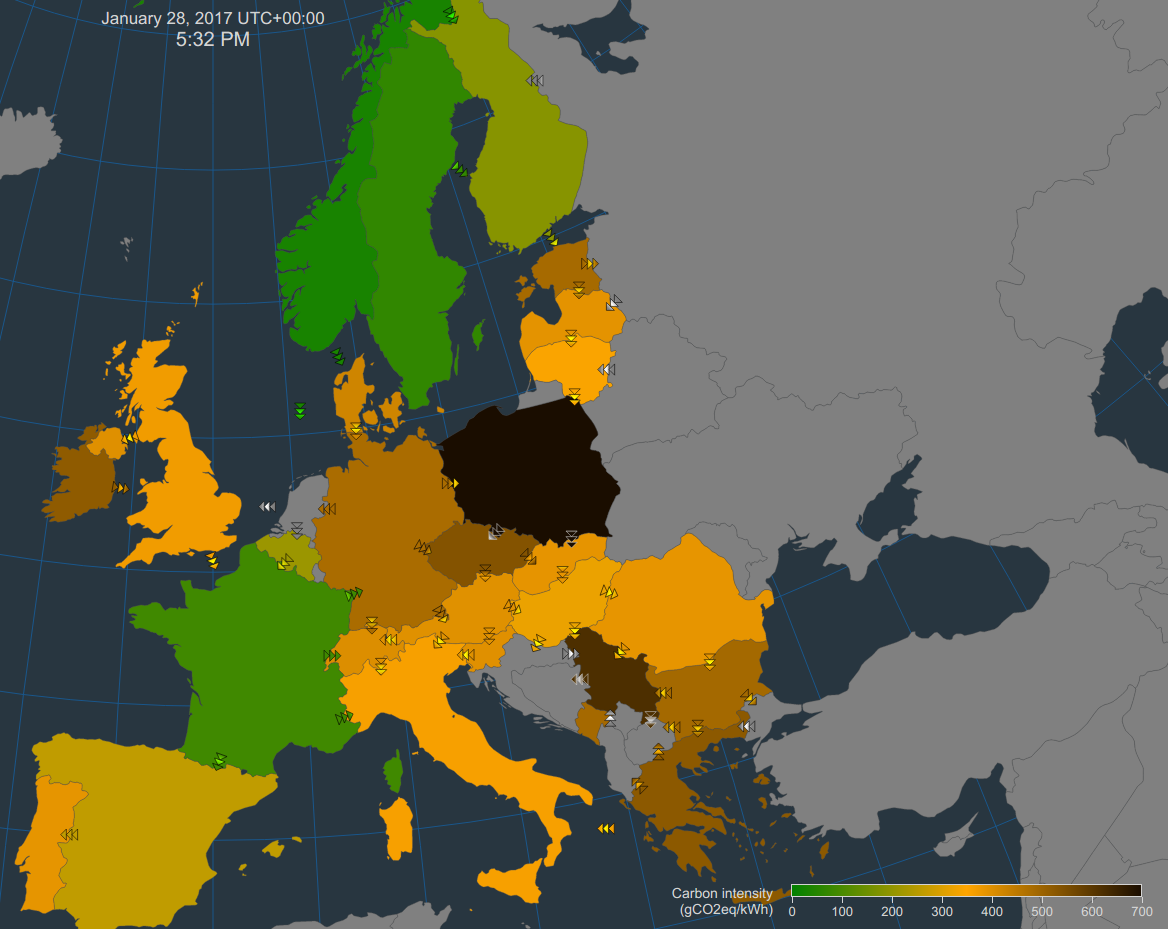

A 21st Century Energy Policy, Part 3: The Technology of the Future

If humanity is to have any hope of avoiding catastrophic climate change, developed countries must take aggressive steps to decarbonise as quickly as possible. This will mean not only replacing existing fossil-fuel power plants, but greatly expanding all electricity production to replace gas and petrol. Such a task demands not just an energy policy, but a comprehensive economic plan.

A 21st Century Energy Policy, Part 2: Nuclear Powered Socialism

As described in the previous article, renewable energy will not be able to provide the backbone of Britain’s electricity supply. If fossil fuels must be abandoned and renewable energy isn’t up for the task, that leaves nuclear power. Nuclear power is, today, almost universally reviled by the left, which views it as dirty, dangerous, and expensive. The truth is, it need be none of these things.

A 21st Century Energy Policy, Part 1: All that’s Wrong with Renewables

With the exception of Arthur Scargill, most on the Left agree that the days of fossil fuels must soon come to an end. But if we are to wean ourselves off of coal and other fossil fuels, what will take their place? The answer which springs to everyone’s lips is “renewable energy”. Unfortunately, getting a majority of Britain’s energy from renewable sources is not attainable.