A 21st Century Energy Policy, Part 1: All that’s Wrong with Renewables

I have written a series of four articles discussing Britain’s energy policy for the left-wing Labour-supporting website Left Futures. In Part 1 I explain the limits of renewable energy sources. Part 2 advocates for the role of nuclear power in an energy transition. Various technologies which should be used and policies which should be enacted in order to improve energy efficiency and electrify heat and transport are discussed in Part 3. Finally, Part 4 proposes an ownership framework capable of building the electricity infrastructure needed.

With the exception of Arthur Scargill, most on the Left agree that the days of fossil fuels must soon come to an end. Whatever nostalgia some may have for the Miner’s Strike, we all know that it would be environmental catastrophe to revive the coal industry. But if we are to wean ourselves off of coal and other fossil fuels, what will take their place?

The answer which springs to everyone’s lips is “renewable energy”. Jeremy Corby has promised to have 65% of electricity coming from renewable sources by 2030, with a longer term goal of 85%. There is also a promise to phase out coal power plants by the early 2020s, strive to keep 80% of global fossil fuel reserves in the ground, and create 300 000 jobs in the renewable energy supply chain. All of this chimes well with the calls for a Green New Deal which have been coming from progressives since the financial crisis of 2008.

But there are two problems. First, it’s not enough. Given that there are some sectors (such as agriculture, steel, and concrete production) which would be difficult or impossible to decarbonise, we must have greater reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from electricity than 65, or even 85, percent. Ultimately, it will need to be 100% and it will need to be achieved as quickly as possible. Second of all, even a target of 65% renewable electricity is not achievable for Britain.

To date, the following types of renewable energy have found extensive use: hydroelectric, wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass. Of these, hydro, geothermal, and biomass energy are able to provide stable, base-load energy supplies. Hydro-power is the best-established of these technologies and provides the vast majority of electricity in Norway and parts of Canada. However, it requires specific geographical features to be viable. As such, only a few hundred megawatts of new hydro capacity could be built in England and Wales. Scotland has somewhat more potential, with a few gigawatts of new capacity possible, but only a fraction of this would be viable in practice. Furthermore, it is still only a few percent of the UK’s 50-60 gigawatt peak power consumption. The role of geothermal energy in the UK is unclear: a renewable industry group estimates that it could provide up to 20% of the country’s current electricity needs and be used very effectively to heat homes, while others have suggested that it is an impractical power source for Britain. Even in the former case, however, other energy sources will be needed. Biomass power (largely consisting of burning wood-chips) is expensive and of dubious environmental benefit. While it is claimed to be “carbon neutral”, this is untrue on the time scales relevant to mitigating global warming. In fact, it can release more GHGs than fossil fuels.

That leaves solar power and wind. Given the relatively high latitude of the UK, general cloudiness, and fact that energy consumption is highest at the times of day and year with the least sunlight, solar panels are massively unfit as an energy source in this country. Furthermore, solar and wind are known as intermittent energy sources, as their output varies, often in an unpredictable manner. This makes them considerably more difficult to manage than conventional power plants. In an electricity system with other energy sources that can be turned on and off, intermittent energy sources could provide a significant minority of the supply. However, as their share grows, you begin to run the risk of brownouts. Thus, it becomes necessary to both build excess generating capacity and to build storage capacity. This way, when the sun is shining and the wind is blowing, some of the energy can be set aside for when it’s dark and calm. Unfortunately, at present, we do not have technologies capable of economically delivering storage at the scale needed. Stepping back to examine the how vast this scale is, it is questionable if sufficient technology will ever exist.

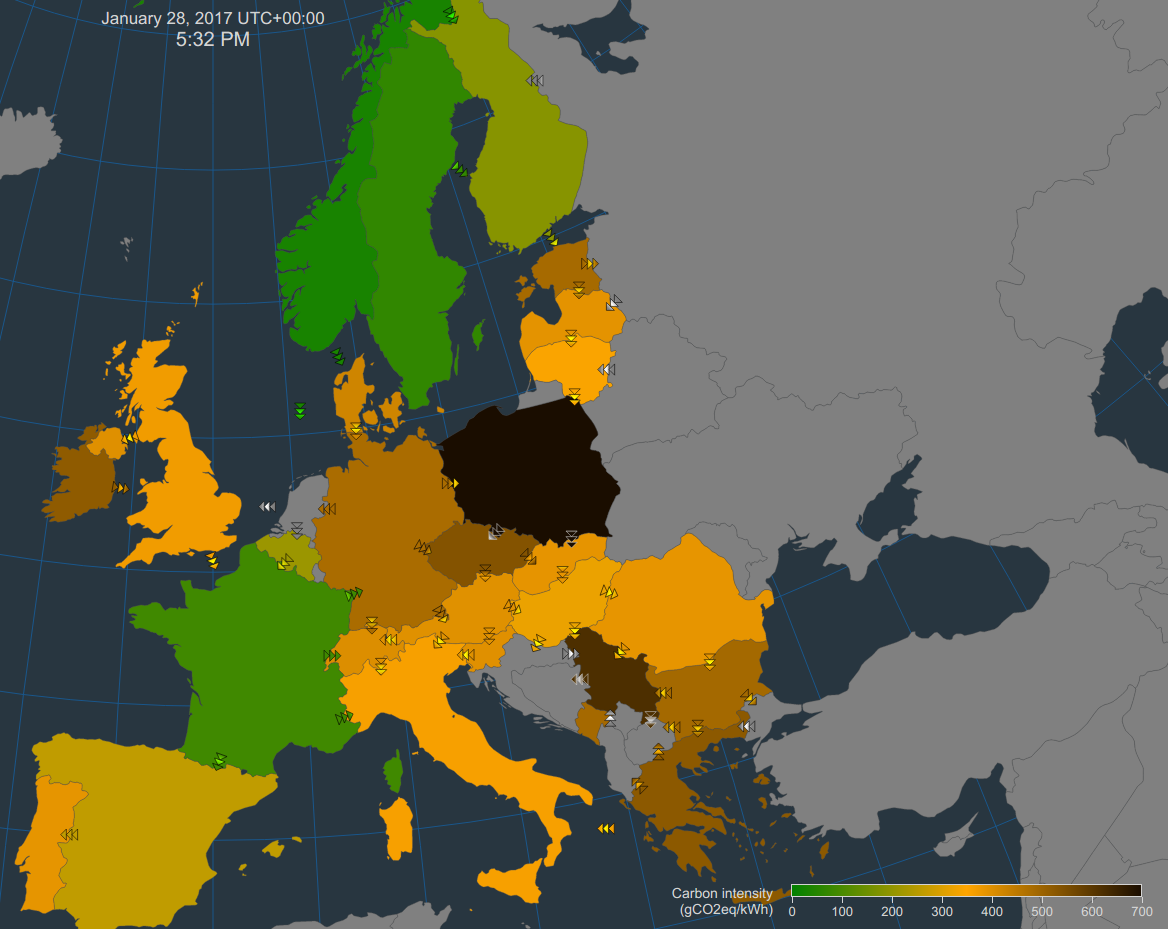

One of the standard responses to this is the suggestion of building a Europe-wide smart-grid. While this may help even out some of the most extreme troughs in generation, it is still insufficient. There is a great deal of correlation between wind-speeds across the continent, so that at times when the wind isn’t blowing much in Italy, it also won’t be blowing much in Denmark, Germany, the UK, or anywhere else on the continent. The net result is that for wind energy to be a major component of the electricity supply, massive amounts of more reliable generating capacity are also needed. The eye-catching headline about Germany generating the majority of its electricity from renewables on some day in July miss the point that it fails to generate this much on most other days.

Given these problems, how have even existing levels of intermittent renewable energy proven economical? What about all the people and companies we hear about running completely off of renewable energy? While it is, strictly speaking, true that such customers are paying for all energy they consume to be produced by renewable sources, that is not to say that the electricity they use at a given time was from a renewable source. There would be times when they’re consuming electricity generated from nuclear power or fossil fuels. It’s just that at other times, the company they’re buying energy from is producing more electricity than needed, which is then sold to other consumers, reducing the need for fossil fuel power plants at that time. This is all well and good for a consumer who wants to feel smug about their purchasing decisions, but isn’t of much use if the goal is powering an entire country (let alone the world) with renewables.

Furthermore, despite the starry-eyed praise often heard for Germany’s “democratic” energy system, the truth is less than pretty. It is true that a number of municipalities have bought back their energy grids and that there are a number of energy co-ops. However, the vast majority of the renewable capacity is owned by private companies and individuals. The feed-in tariffs used to incentivise investment in renewable energy are set well above market energy prices and have led to the highest or second highest energy prices in Europe, while enriching investors and those well-off enough to own a home on which to install solar panels. And yet, Jeremy Corbyn slammed the Conservatives for cutting feed-in tariffs. Worse, the actual reductions in GHG emissions is underwhelming. Assuming that Germany meets its targets (which is dubious), it plans for 80% of electricity to be renewable by 2050. On the other hand, France was able to move a similar proportion of its electricity production to low-carbon sources in a decade.

Most damming of all, there simply are not enough renewable energy sources in Britain to meet our needs. To come close would require using every available technology (many of which are unproven or expensive) and massive amounts of land. There would be essentially no remaining wilderness and generating capacity would need to intrude massively upon living areas. More realistic estimates suggest that renewables can provide just a fraction of Britain’s power.

All of this makes renewables insufficient if our goal is to decarbonise our energy production. The problem becomes even worse when considering that currently electricity makes up only 20% of Britain’s energy usage. Even with efficiency gains, electricity production will have to grow massively if it is to heat homes, fuel cars, and power trains, and it does not appear that renewables are up for the task.

Much of the appeal of renewable energy seems to come from a “small is beautiful” approach to electricity production. Many people find the idea of having a distributed energy system made up of individuals, small businesses, and co-operatives to be appealing. It only goes to show how much neoliberalism has altered the left’s thinking, that this is considered a progressive approach. A market of many small producers has more in common with Adam Smith than with any strain of socialist thought. Such a policy would be insufficient to fight climate change, not be able to provide a reliable electricity supply, and enrich a few well-to-do owners of solar panels and wind farms at the cost of higher electricity prices for everyone else.

comments powered by Disqus