A 21st Century Energy Policy, Part 2: Nuclear Powered Socialism

I have written a series of four articles discussing Britain’s energy policy for the left-wing Labour-supporting website Left Futures. In Part 1 I explain the limits of renewable energy sources. Part 2 advocates for the role of nuclear power in an energy transition. Various technologies which should be used and policies which should be enacted in order to improve energy efficiency and electrify heat and transport are discussed in Part 3. Finally, Part 4 proposes an ownership framework capable of building the electricity infrastructure needed.

As described in the previous article, renewable energy will not be able to provide the backbone of Britain’s electricity supply. Geothermal power might provide a minority of the baseload capacity, it may be worth building new hydroelectric dams where possible, and there is a place for some intermittent energy capacity, but this still requires a substantial portion of the supply to come from another source. If fossil fuels must be abandoned1 and renewable energy isn’t up for the task, that leaves nuclear power. Nuclear power is, today, almost universally reviled by the left (with the notable exception of the Communist Party of France). It is viewed as dirty, dangerous, and expensive. The truth is, it need be none of these things.

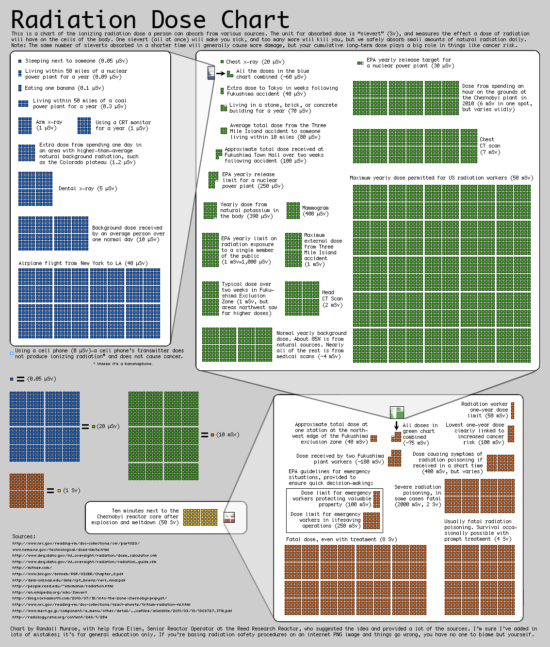

Much of the fear around nuclear power comes from not understanding the science and risks of radiation. It is notable that scientists tend not to be afraid of radiation and are significantly more in favour of building nuclear power plants than the general population. The fact of the matter is that the extra radiation experienced by people living near a nuclear power plant is insignificant in comparison to background radiation, as can be seen in the chart below.

The threat of accidents has also been greatly overblown. The major accidents which are cited are Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima. The consensus among peer-reviewed studies is that the Three Mile Island accident led to few or no deaths. The causes of the accident have been thoroughly investigated and reactor design and operating procedures have been improved as a result. Chernobyl, far and away the worst of these incidents, was the fault of a uniquely bad reactor design and a poorly executed experiment. RBMK reactors, such as the one at Chernobyl, are known to be unstable, had a control rod design which initially increases the reaction rate, are surrounded by flammable graphite, and lack the containment buildings seen in all other nuclear power plants. An accident like that at Chernobyl would not be physically possible in the types of reactors used in the West.

Fukushima is the most recent of these and has resulted in a renewed backlash against nuclear power. It is important to remember that this event was initiated by an a 13m-15m tsunami resulting from a magnitude 9 earthquake, neither of which are events which can strike Britain. Furthermore, the private operator TEPCO had been cutting corners in terms of disaster preparedness. Clearly, strong independent oversight is needed for nuclear power and reactors should be in public ownership to make corner-cutting less likely. However, Fukushima is not an indictment of nuclear energy per se. No one died from radiation poisoning and any increase in cancer deaths looks set to be very small (even when using pessimistic models) and difficult to separate from background rates. As with Chernobyl, mental illness is a bigger threat to the effected population.

Obviously every death is tragic, but no energy source is without risks. Despite its scary reputation, nuclear power has the lowest or second lowest number of deaths per gigawatt-hour of any energy source. When things go wrong, they tend to do so in a big, scary way, which misleads people as to the threat. New reactor designs (and, indeed, some older ones such as the CANDU) include “passive safety” features which do not depend on human or electronic intervention, making accidents like those at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima physically impossible.

The other big argument against nuclear power is what to do with the waste. It is important to keep this problem in perspective. Currently, only 25ml of high level nuclear waste (the stuff which needs to be stored for thousands of years) is produced per person, per year in Britain. Even if all of the UK’s present energy demands were met by nuclear, it would produce about a pint of high level waste per person, per year. This is a small volume to deal with when compared to other forms of waste. We can keep the waste in dry cask storage indefinitely as we look for longer-term solutions, so unlike GHG emissions this is not a pressing issue. Ultimately, burying nuclear waste deep in dry, geologically stable regions looks to be a viable solution. Furthermore, Generation IV reactor designs promise to be able to use existing nuclear waste as fuel and produce much lower volumes of their own waste.

There is no denying that many nuclear projects have been expensive. New reactor designs have been known to go over-budget. On the other hand, while results of studies examining energy costs vary greatly (see the Wikipedia article), they tend to show that overall nuclear is of comparable cost to other energy sources. In recent years it can appear that renewable energy is cheaper, but these studies do not seem to take into account requirements for storage and changes to the electricity grid. Nuclear power plants have large capital costs and low operating costs, which means that building them in the private sector requires expensive subsidies. Nuclear-dependent France has middling to low electricity costs and demonstrates the savings which can be achieved by building reactors through a public sector energy monopoly to a standard design. In the future, small modular reactors could potentially be mass-produced, bringing prices down further. While no clean energy source is cheap, nuclear is likely to be the cheapest option for countries without hydroelectric or geothermal capacity.

While most leftists are today opposed to nuclear energy, ironically it is only within a left-wing comprehensive economic plan that nuclear power can reach its full potential. The energy transition of France in the 1970s and 1980s shows what can be achieved by a state intent on transforming its power supply. For a country to prosper, it must have a clean, reliable, abundant energy supply and renewables alone will not provide this in Britain. If socialism is to bring prosperity, rather than a more equitable distribution of misery, our socialism must be nuclear powered.

-

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology is sometimes invoked as a way for us to continue using fossil fuels. The issue with it is how we go about ensuring that the captured CO2 stays where we put it. Usually it is suggested that it be stored underground, but were it to leak then it would undo all of our work capturing it in the first place. In many ways this is a more concerning problem even than nuclear waste, since the latter is solid—making it much easier to contain than a gas—and needs to be stored for only a finite time. ↩

comments powered by Disqus