Labour Policy Responses: Environment, Energy and Transport

In response to the recent publication by the Labour Party’s National Policy Forum (NPF) of various policy statements, a number of us on the Labour Left have written responses. My response on environmental, energy, and transport policy was published on Left Futures. This is the longer, original version. I have have also produced another version of this report which is more suited for use amending or replacing parts of the NPF’s document, taking into account comments received on my article. Thanks you to David Pavett for his comments and suggestions.

The National Policy Forum has made the strange decision to group culture with the environment and energy. Meanwhile, transport is placed, not completely without justification, with local government and housing. However, as transport is a major consumer of energy and a transport policy will be essential to fighting climate change, I decided to address it along with energy and the environment, in place of culture.

Climate Change

The NPF document rightly identifies climate change as one of the greatest challenges of the century. However, beyond this, it has little to say. It refers to the Paris Agreement of 2015, but does not acknowledge that the stated goal of keeping warming below 2°C, or even 1.5°C, is not going to be achieved with the emissions commitment which were made. Nor is the magnitude of the challenge of keeping temperatures below those limits recognised. It seems inconceivable that it could be done without state-directed economic planning on a scale previously unseen in the West during peacetime.

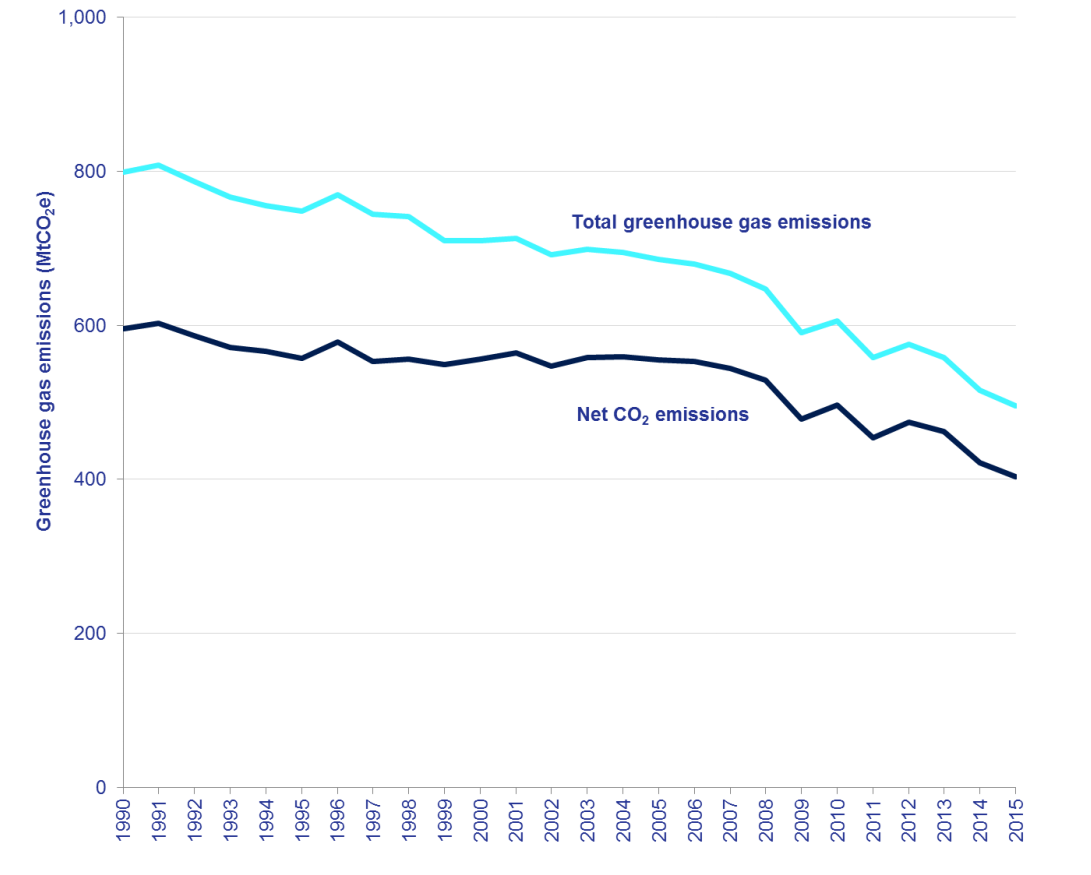

The NPF believes that “Labour has a strong record in pressing for and tackling climate change.” While it is true, as they say, that Labour passed the Climate Change Act in 2008, this was also supported by all but three of the Tories. The actual reductions in emissions during Labour’s time in government were not much different from what occurred under John Major and the Coalition (see Figure 1) and did not come close to what is necessary. A recently published climate plan required global emissions to fall by half every decade until at least 2050 and a developed country like Britain will be required to making even faster cuts than that. If it is felt that this is unachievable, then we need to be upfront about that and begin preparing for the negative impacts of climate change.

Three omissions by this policy document should be noted. The first is its failure to mention high-potency greenhouse gases such as methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases. When weighted for global warming potential, these make up nearly 20% of UK emissions, with methane being the most significant. Typically, emissions of these gases are easier to prevent than those of carbon dioxide, so rapid action should be taken to reduce them. Secondly, no reference is made to the use of “negative emissions” technology, which most plans for combating climate change now require. This involves planting trees, burning them, and sequestering the released carbon underground. Finally, the effect of land use changes (e.g. deforestation, conversion to agriculture) is not mentioned, although at least one climate plan requires net emissions from this to reach zero by 2050. Overall, it appears that the authors of this document know little about climate change and have vastly underestimated the magnitude of the challenge it now represents.

The closest the NPF comes to suggesting actual policy is to commit that “By investing £500 billion in infrastructure backed up by a publicly owned National Investment Bank and regional banks we will build a high-skilled, high tech, low carbon economy to help generate a million good quality jobs.” Lacking any details of what sorts of investments are involved, this pledge is useless. Where specific sectors, such as energy, are mentioned, no solutions are proposed. In the following sections, some priority sectors will be examined in closer detail. In the following sections, some priority sectors will be examined in closer detail and some broad policies put forward.

Energy

More than once, the NPF comments on the importance of decarbonising energy while at the same time tackling energy bills. The obvious tension between wanting to “curb energy bill rises” while at the same time invest in new energy infrastructure is never acknowledged. While it is said that the “energy market is in need of reform”, what this reform would look like is never stated. Indeed, the very existence of a market in energy is never questioned; despite widespread support for renationalisation, the most the NPF has to say on this issue is calling for a “National Investment Bank to promote public investment and community ownership across future energy solutions”.

Although acknowledging that “A fully costed low carbon energy platform that includes renewables, nuclear and green gas should be developed and publicly financed options should be considered to ensure that the UK has a low carbon economy that works for consumers moving forwards”, no effort has been taken to do this. As I have argued elsewhere, any realistic decarbonisation plan will need to rely heavily on nuclear energy. Although this would be an unpopular proposition among many on the left, we need to face up to the impossibility of powering Britain solely off of her own renewables.

Nuclear power can be most effectively deployed by the state using a standardised design, adding another argument for nationalisation. A similar argument could be made about renewable power sources. As I have argued in the past, a new Power Generation Board (PGB) should be created out of existing nuclear and renewable capacity and be given control over the national grid. This would go some way to ending the absurdity which is the market in electricity and would give the stability needed for the PGB to make long-term investments

To eliminate fuel poverty, progressive tariffs could be used. This would see every household given a minimum amount of electricity at low or zero-cost, with the price per additional kilowatt-hour rising to current levels and above depending on how much is used in a given month. The price bands could be structured such that high-use customers are effectively paying for the electricity of low-use customers and this system would not be a cost to the government. However, for this to work, all consumers would need to be buying from the same electricity supplier. As such, supply and distribution should also be nationalised and either folded in the PGB or passed to a devolved body.

Little is said in the NPF document about non-electric energy use. As electricity only represents 29% of greenhouse-gas emissions, this is a glaring omission. “Green gas” is mentioned and this could be introduced into the gas supply as a short-term measure to reduce emissions from heating. Some hydrogen could also be added and, if appliances are converted, the gas supply could be switched entirely to hydrogen. However for new houses (and, in the mid-term, for existing ones), better energy efficiency can achieved using electric heat pumps. Transport will also need to be electrified and this will be discussed in more detail below.

Finally, nothing is said in the document about energy efficiency. All new homes should be built to the highest standards of insulation and, to the extent feasible, old homes should be retrofitted along these lines. New home designs should try to maximise daylight and heat from the sun. Even in the NPF document on housing, such things are not considered. Appliances should be subject to strict efficiency requirements and the government could create a program to buy old, inefficient models back from citizens.

Agriculture

Agriculture is included in environmental policy, although the main focus of the NPF draft seems to be on the issue of subsidies post-Brexit. I will leave this issue to someone who knows more about agricultural economics. However, it might be worth considering whether a system of supply management could replace subsidies. This would involve farmers selling to marketing boards which they run in partnership with the state. The marketing boards then operate a monopoly on wholesale and return any profits to the farmers. For the overall system to be effective, controls would be required on imports and exports of the managed agricultural products, which may not be possible depending on the UK’s relationship with the EU.

Agriculture is also a major source of greenhouse gases, making up 10% of the UK’s total. These are mostly in the form of methane and nitrous oxide. The former is produced in the digestive systems of livestock (particularly cattle) while the latter comes from the use of fertilisers. While this is not an area which I am greatly knowledgeable about, measures such as more precise application of fertiliser, better soil management, different crop rotations, new animal feeds, supplements to animal feeds, and breading could all play a role. Any agricultural subsidies should be made conditional on farmers taking action to reduce their emissions.

Transport

The only policies which can be found within the NPF report on transport are to take “the railways back into public ownership” and “give local authorities franchising powers to run and manage their local bus routes”. While the inadequacy and expense of public transport are acknowledged, there are no concrete proposals to tackle either.

Rail

While the commitment to bring rail franchises back into public ownership is laudable, there are many other questions to be answered about rail. First, what is to happen to the Rolling Stock Companies (ROSCOs) which lease the trains to the franchise operators? These are obscenely profitable, take essentially no risk, and have failed to adequately invest in new rolling stock. While nationalising franchises would cost essentially nothing, the ROSCOs would be quite expensive. One approach would be for the government to regulate them and trim the profit margins. Where new rolling stock is introduced, it should be publicly owned. As decarbonisation demands a campaign of rail electrification, plenty of new stock will be required. It would be worth considering recreating British Rail Engineering Limited to build this in-house.

Network Rail present another question. Currently it provides a hidden subsidy to the train operators by charging artificially low track access fees. The difference is made up by a government grant and borrowing. With each infrastructure upgrade, its debt continues to ballootheytheytheyn. While not sustainable, this has led to increased investment compared to the days of British Rail, when funding was at the whim of whoever was in government. A new model is clearly needed, but what it should be is unclear. Furthermore, the question of exactly what new investments are needed in rail (e.g. electrification) needs to be addressed.

A final consideration for rail is how a newly nationalised sector should be structured. It has been suggested that the railways should be more decentralised than they were under British Rail. Allowing large local authorities to manage commuter rail, in the model of London Overground, does seem reasonable. However, devolving regional rail services risks continuing the fragmentation which has marked the sector since privatisation. Perhaps a compromise would be to have trains operated by a single national company but allow local and regional governments to be represented in the administration of regional routes.

Buses

It is welcome that the buses are acknowledged by the NPF and giving local authorities more control over service is undoubtedly a good idea. However, it is unclear what exactly is meant by “franchising powers to run and manage their local bus routes”. Presumably it refers to a system such as that in London where, even if a private company operates the buses, they do so under contract with a local authority, which sets and collects fares, determines routes, etc. Private operators will fight attempts by local authorities to do this, so the process should be tilted in favour of the councils. Additionally, funding should be provided by central government to help buy or create council-owned bus companies. There should also be an emphasis of integrating buses and local transport with the rail system. Regional and national buses were not mentioned by the report. These should also be re-regulated and, preferably, taken back into public ownership. There may be a role for devolved administrations to play in the management of these services. New buses should be electric, either being trolley-buses or battery powered.

Other Public Transport

No reference at all is made to other forms of transport. It is worth considering whether current ferry services are adequate and whether these should be brought back into the public sector. Ferry service could be integrated with rail so as to provide a seamless alternative to flying. Rationalising air routes would also go some way to reducing emissions from aviation, suggesting that renationalisation of airports and re-regulation of airlines should be on the table. It would be worth considering whether a rail tunnel could be built to Ireland to replace many flights.

A running theme through all of this has been the need to integrate transport across jurisdictions and modes. This would make public transit a more viable alternative to driving and flying. There is a strong argument for making local transport free at the point of use, to make it more accessible to those on low incomes and to encourage use by everyone. Regional and national travel would still require fares, but a single, simple ticketing system should be adopted across the entire country for buses, trains, and ferries, allowing trips to be planned and purchased in a single place.

Private Vehicles

Private transport goes completely unmentioned by the NPF. While an affordable and comprehensive mass transit system will go some way to reducing the use of private automobiles, it obviously can not eliminate it. A date should be set beyond which all cars sold in Britain must be zero-emissions vehicles. For this to be practical, an expansion in charging infrastructure is needed for electric cars. Fast charging stations could be placed at existing petrol stations, while (cheaper) slower ones could be placed in car-parks. A public electrical company would be ideally placed to operate these. Widespread adoption of electric vehicles would also be useful in levelling out peaks in electricity demand, as owners could program them to charge when demand is low (e.g. overnight) and, if necessary, feed some of their energy back into the grid when demand is high.

Conclusion

Climate change is perhaps the greatest threat humanity has ever faced, and mitigating it will be a task similar in scale to the conversion to a wartime economy. The NPF displays no awareness of this fact and has made no effort to draw up the detailed plans which will be required. Instead they have contented themselves with vague, feel-good slogans while ignoring crucial areas of climate policy. If Britain and the rest of the world continue to take such an approach, then climate change will be a catastrophe and perhaps even an existential threat to future generations.

comments powered by Disqus