Why Social Democracy Was Great and Why It Isn’t the Answer

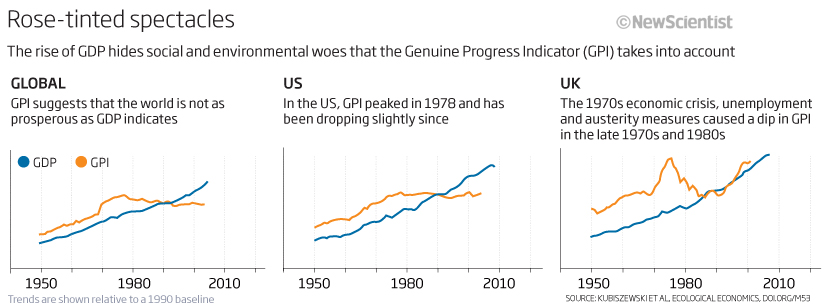

Yesterday I happened to read two very interesting articles, which at first glance would appear to be entirely unrelated. One was in New Scientist magazine and explained that, although GDP has risen fairly steadily in the west for the past several decades, the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) has slowly been declining since 1978. The GPI essentially tries to adjust the value of GDP to account for social and environmental problems (such as inequality and pollution). The other article was an opinion piece in The Guardian by two Canadian academics and activists that I am rather fond of: Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin. Here they explained why we can’t expect any attempt at a second New Deal in Europe as a way of combating the economic crisis: in short, without a threat of something more radical (ie: all-out socialism), the ruling classes see no need to engage in progressive economic policies.

This set of graphs, taken from New Scientist‘s website, shows that global GDP

and GPI rose fairly steadily from 1950 to the late 1970s.

This corresponds with the period in which Keynesianism ruled. This usually

took the form of social democracy: public ownership of key industries, strong

trade unions, lots of regulation, a large welfare state, etc. As Panitch and

Gindin explain, the reason that this could be implemented was because there

were powerful working-class forces at work which could have led to the outright

abolition of capitalism. Faced with the prospect of losing everything, the upper

classes were willing to sacrifice a little wealth and power in order to pacify

the lower classes. This also was reflected in American foreign policy: the US

established the Marshall Plan in Europe to ensure that capitalism survived

there, thus helping to ensure its survival in the USA as well.

This set of graphs, taken from New Scientist‘s website, shows that global GDP

and GPI rose fairly steadily from 1950 to the late 1970s.

This corresponds with the period in which Keynesianism ruled. This usually

took the form of social democracy: public ownership of key industries, strong

trade unions, lots of regulation, a large welfare state, etc. As Panitch and

Gindin explain, the reason that this could be implemented was because there

were powerful working-class forces at work which could have led to the outright

abolition of capitalism. Faced with the prospect of losing everything, the upper

classes were willing to sacrifice a little wealth and power in order to pacify

the lower classes. This also was reflected in American foreign policy: the US

established the Marshall Plan in Europe to ensure that capitalism survived

there, thus helping to ensure its survival in the USA as well.

As you can see from the above plot, these policies were quite successful at ensuring increased quality of life for all. However, the welfare state was always dependent on the success in the private sector for revenue (with a few exceptions, nationalised industries were not used as major revenue sources). Thus social democracy has always been dependent on continued capital accumulation. And this was its fundamental weakness. When the global slump came in the 1970s (in Britain it was so severe that you see a large decrease in GPI around 1975) it began to put the welfare state in jeopardy. In some countries there were attempts to break away from the dependence on private capital accumulation (the Meidner Plan in Sweden and Mitterrand’s nationalisation of banks in France) but the working class was not strong enough to bring these attempts to a successful conclusion. In all countries it eventually proved necessary to start scaling back the welfare state and, to one degree or another, abandon Keynesian policies in favour of Monetarist ones. This new economic orthodoxy is usually referred to as neoliberalism.

In Britain this took the form of Margaret Thatcher. In the US it was Ronald Reagan. In Canada it was Brian Mulroney. All of them implemented policies which were harmful to the average citizen. Trade unions were weakened and could no longer act as a force against income inequality. Industries previously devoted to the public good were privatised and used to enrich a select few. Cuts to social spending hurt the poor by making once universal services available only to those that could pay. Deregulation made it easier for companies to pollute the environment and the emphasis on private profit meant that environmental costs were ignored. The reasons for declining GPI are clear. What is less clear is what to do about it.

Panitch and Gindin show that today we lack the popular forces which made social democracy viable in the post-war period. There are no significant examples of non-capitalist states and few radical trade unions. In the minds of most people there is no alternative to capitalism. Anti-capitalist parties are small and marginal (with a few exceptions, such as in Greece and, to a lesser extent, Spain and Portugal). The business class need not fear the imposition of socialism; they know that the working class is currently too disorganized to be a serious threat and thus see no need to pursue a policy of appeasement.

Now, this situation will very likely change in the coming years and decades, but there are a few questions we should address as we work to create new working-class institutions. One is what these movements should demand. Many progressive economists talk about things like reregulating the banks and implementing a Tobin tax. However, as explained above, we are unlikely to be able to impose these reformist measures without the threat of something far more radical. And, knowing what happened the last time the left settled for reforming capitalism rather than abolishing it, we should not be content merely to use socialism as a threat. This time we must implement it. Social democracy died in the 1980s and there is no point in trying to bring back the dead. Rosa Luxemburg’s sentiments are more true now than ever: “Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to Socialism or regression into Barbarism.”

comments powered by Disqus